The geometry of change

A fascinating study published in the journal Nature Communications written by Dr. Alexa Mousley, Dr. Richard Bethlehem, Dr. Fang-Cheng Yeh and Dr. Duncan Astle from the University of Cambridge has rewritten the chronology of human brain development. Instead of viewing aging as a gradual decline, researchers have identified five major structural phases in the brain, each separated by critical moments of change called topological turning points. This work compels us to think of the brain not just as a mass of tissue, but as a complex communication network, comparable to an interconnected roadmap, whose structure can be analyzed with advanced mathematics.

To grasp the magnitude of this finding, it is essential to delve into topology, a branch of mathematics often nicknamed the "rubber sheet geometry" or "geometry without measurement." Unlike traditional geometry, which focuses on properties involving precise measurements such as length or area, topology studies the properties of objects that remain invariant (unchanged) even if the object is deformed, stretched, or twisted, provided it is not cut or glued. The classic example is the topological equivalence between a donut and a coffee cup: although their shapes are very different, both have exactly one "hole" (a loop), and that essential property does not change.

When we apply this tool to the study of the brain (network neuroscience), we are not interested in the exact shape of a neuron, but in the fundamental organization of the connections between all regions. Brain connectivity is modeled as a network or graph, where functional regions are the nodes and the white matter fiber bundles that connect them are the edges or connections. Topology allows us to abstractly quantify the architecture of this network using metrics such as segregation, which measures the extent to which regions form highly interconnected working groups to perform specialized tasks, and integration, which measures how efficiently and quickly information can be transferred between any pair of nodes. Centrality is another key metric, identifying which nodes are the most influential for information flow.

The topological turning points, therefore, represent the central findings of the research. They are moments of abrupt and fundamental change in the organization of the brain network, detected when the combination of these topological measures transitions from being statistically characteristic of one epoch to being characteristic of the next. In simple terms, topology allows neuroscientists to measure the essence of how the brain is wired at every phase of life.

To identify these epochs, scientists used an advanced magnetic resonance technique called Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI), which measures the movement of water within tissues to trace the course of white matter fibers. Subsequently, they applied sophisticated topological algorithms to quantify the network architecture in thousands of individuals throughout their lives, thereby revealing the patterns of human topological maturation.

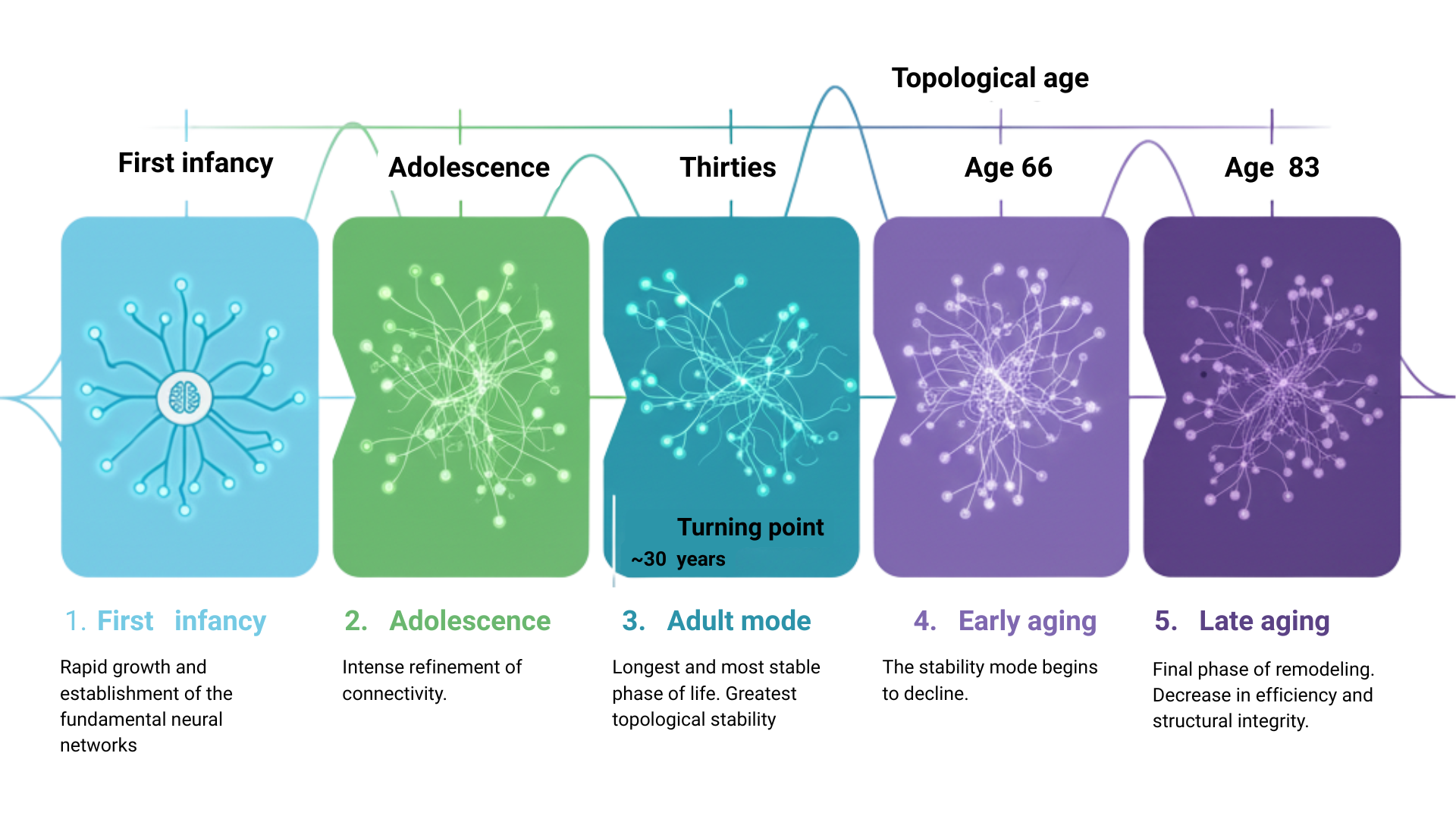

The analysis of these patterns revealed the following five main phases, each with distinct topological characteristics. The first stage, early childhood (or first infancy), spans from birth to adolescence and is characterized by a period of rapid growth and establishment of the fundamental neural networks. During this phase, the network works intensively to form and consolidate essential connections, building the foundations of the future brain architecture.

Early Childhood is followed by adolescence, a critical period distinguished by an intense refinement of connectivity. At this stage, the volume of white matter—the "cables" linking brain regions—continues to increase, resulting in the maturation of the network. Communications between different brain areas become faster and more precise, enhancing global efficiency and information processing, which is fundamental for complex cognitive development.

The first crucial turning point occurs in the early thirties (around age 30), marking the transition to the adult mode. This is the longest and most stable phase of life. The brain architecture reaches its greatest topological stability, meaning the network maintains an ideal and robust balance between integration (efficient global communication) and segregation (the formation of specialized modules). This structural optimization is what enables adult cognitive function.

The second turning point, near age 66, initiates the early aging phase. Here, the topological stability of the adult mode begins to decline. Structurally, the network is forced to reorganize to compensate for the first functional losses and the wear of connections. This remodeling gives rise to a new architecture that is no longer as homogeneous as the adult one, but begins to prioritize different communication patterns to maintain cognitive function.

Finally, the last significant change is observed around age 83, defining the late aging phase. In this stage, the structure of the brain network enters its final phase of remodeling. Topological metrics show a decrease in efficiency and structural integrity typical of advanced age, reflecting the changes associated with the decline in general cognitive function.

This "five-epoch" model is crucial because it offers a new perspective for medicine. By having a precise map of what the brain network should look like in every decade of life, scientists can use the brain's topological age for diagnosis, rather than relying solely on chronological age. This can help detect if an individual is deviating from the normal pattern, offering a potential tool for the early detection of neurodegenerative and developmental diseases. The study definitively underscores that the brain is an engineering feat in constant remodeling that goes through critical and well-defined stages throughout our entire existence.

Source

Mousley, A., Bethlehem, R.A.I., Yeh, FC. et al. Topological turning points across the human lifespan. Nat Commun 16, 10055 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65974-8